South Africa Radical Markets

—

layout: post

mathjax: true

title: (My First Post!) Derivatives Portfolio Compression With Deep Learning (Part One)

In my second post, I propose a radical resolution land inequality in South Africa, drawing mostly from ideas presented in Eric A. Posner and E. Glen Weyl’s book Radical Markets.

Background

The Fight For Economic Freedom

The recent history of South Africa is one of a burgeoning economy and of persistent inequalities. While it is the second largest economy in Africa, it is also the most unequal, as a result of the institutional segregation and discrimination that has plagued the country since 1990. Many compounding factors contribute to the maintenance of this inequality; one of which is the vast inequality in land ownership between blacks and whites. According to a recent land audit, 29.1% of land by value is owned by the government and individuals previously disenfranchised by apartheid, a demographic that makes up 92% of the South African population. Much of this inequality is the result of laws that prohibited black ownership of agricultural lands outside of the reservations where they were forced to live.

Despite constitutionally mandated efforts redistribute the land more evenly amongst racial demographics, progress has been slow, due in part to the government’s policy of “willing-buyer willing-seller”, through which the government would buy land from white land owners for redistribution. The inefficiencies of this mechanism are to be expected, as it is vulnerable to the holdout problem commonly associated with voluntary land markets. Many within the country, particularly the far-left political party EFF (Economic Freedom Fighters), have expressed dissatisfaction with present land redistribution efforts. The EFF recently put forth a motion for a constitutional amendment allowing for “land expropriation without compensation” and it was passed by the nation’s parliament in February. The motion has faced scrutiny from commentators within South Africa and abroad, stating that such a departure from traditional property rights would diminish foreign investment and threaten the nation’s already fragile food security. In the rest of this post, I will discuss a resolution for land inequality that avoids the potentially drastic consequences to expropriation without compensation. The ideas below are covered in more depth here.

The Vickrey Commons Mechanism

The Vickrey Commons is a solution to the infamous holdout problem discussed by Posner and Weyl in “Radical Markets”. The concept stems from a utopian vision by Nobel-Prize winning economist William Vickrey: an ideal economy in which all property is constantly up for auction. In his vision, every capital asset that one could own individually must be mandatorily sold if another individual is willing to pay the asset’s posted value. Vickrey, a pioneer in designing auctions which incentivize participants to bid their true values presented the Vickrey Commons as a way to ensure that no individual sets the sale amount of their asset lower than the amount at which they would actually be willing to part with them. If one were to employ this strategy, he would face significant risk of an opportunistic buyer purchasing the asset a price less than its value to the seller. There is a caveat; if price information is entirely public, that is, if prospective buyers and sellers know the posted sale prices of all items in the economy, there is no incentive to refrain from bidding higher than one’s true value in order to achieve the “market price” of the asset a potential seller holds. This a problem Posner and Weyl solve by introducing another powerful mechanism design from another influential economist.

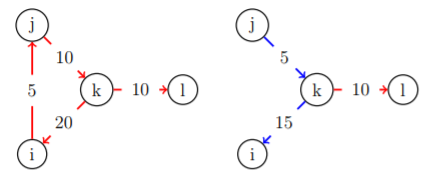

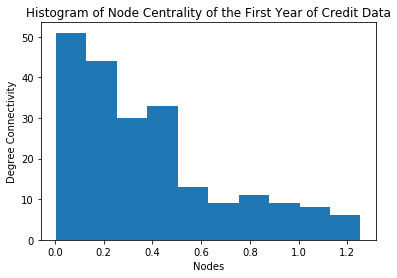

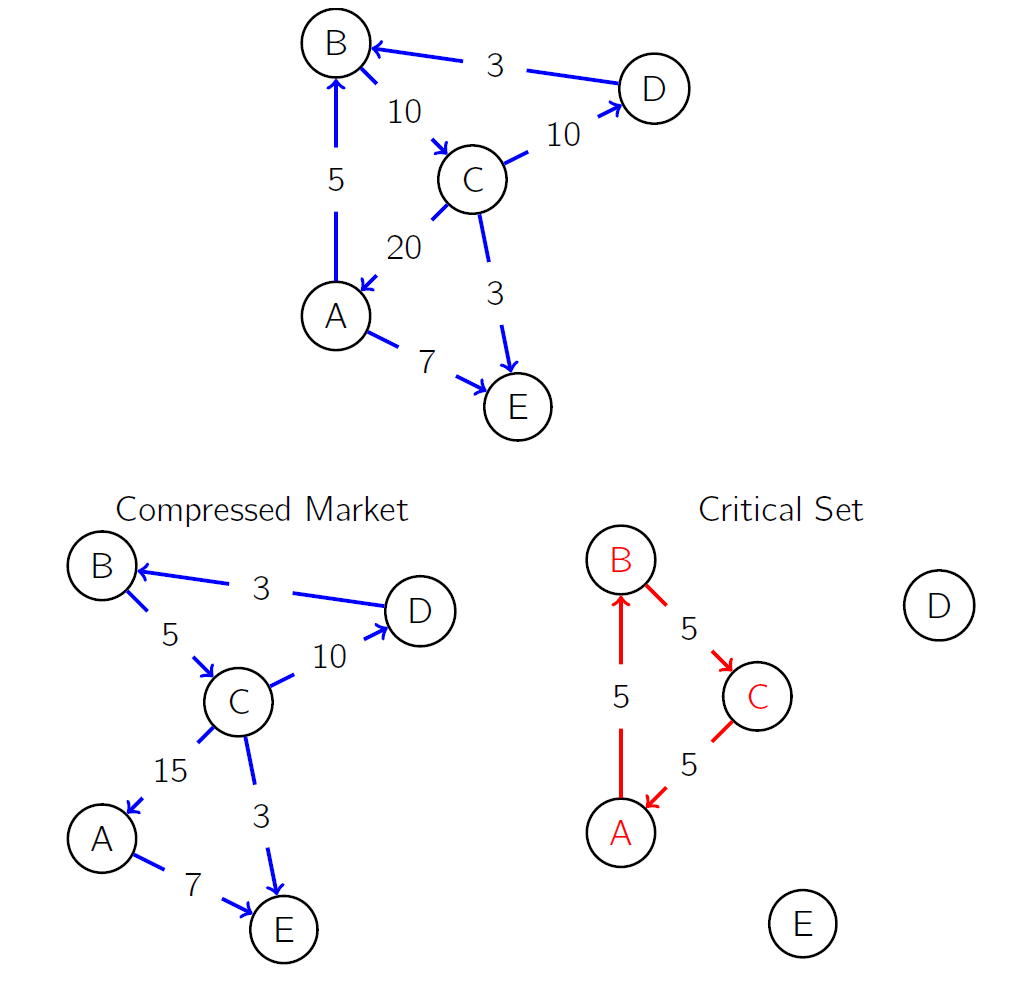

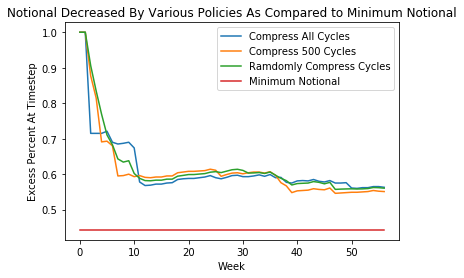

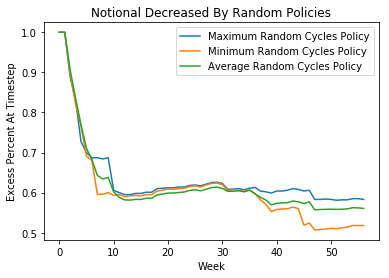

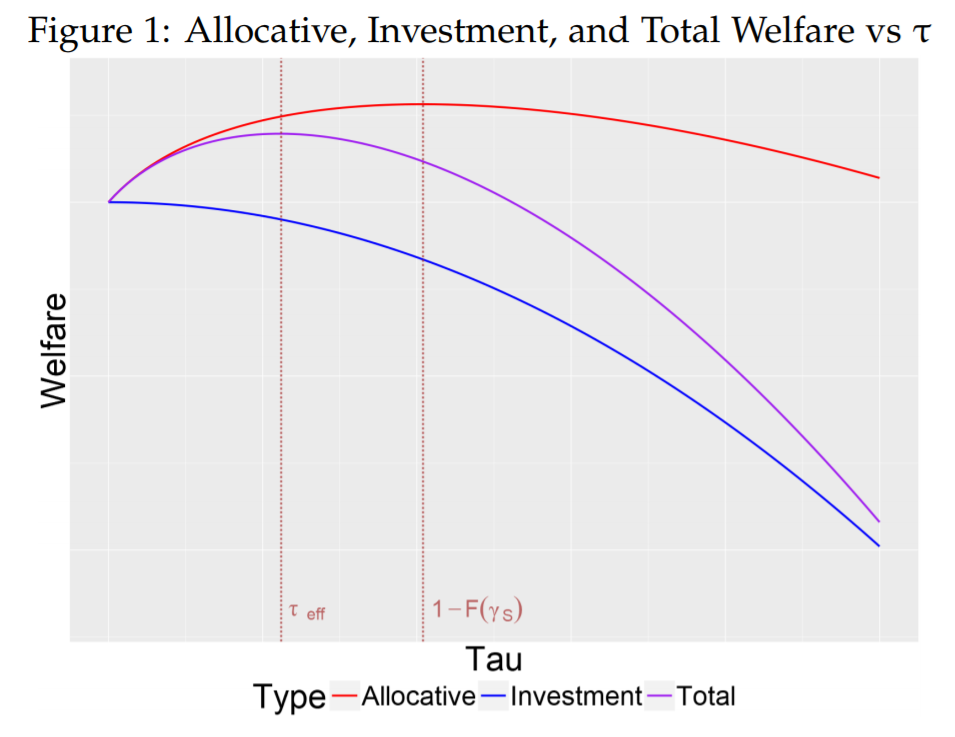

Benefits of a COST

The “Common Ownership Self-Assessed Tax” complements the Vickery Commons and intends to place a tax on wealth that pays for the social cost of (holding) wealth. Much like the Vickrey Commons, the COST has a simple structure, despite its immense utility. Generally placed on assets with common value, a COST is set somewhere between the turnover rate (which can be thought of as the probability that the holder of an asset loses the asset in a given time interval) and zero. When the tax rate is the same as the turnover rate, an asset holder is incentivized to post her true value as the price of the asset. If she sets it higher, she will pay more in taxes than the expected value of holding the asset. However, like any tax, setting the COST too high would disincentive investments that would increase the value of the asset; as the asset holder does not receive the full return on their investment. The trade-off between the allocative efficiency improvement of the tax combined with the Vickery Commons market ecosystem (the ability for individuals to trade efficiently amongst one another unrestricted by holdout problems) and the investment efficiency (the effects of the tax is illustrated in the figure below, from (Weyl and Zheng 2017)). In the figure $\tau_{eff}$ demarks the COST level that maximizes social welfare, the “sweet spot” between turnover rate and zero (which maximize allocative and investment efficiency respectively).

The Vickrey Commons and the COST complement one another to deliver significant welfare gains: The COST disincentivizes individuals from setting their posted price in the Vickrey Commons much higher than its true value (as they will be taxed heftily), while the Vickery Commons disincentivizes people from setting their property value lower than its true value (as it puts them at risk of having their property taken from them without being adequately compensated). In addition, the revenue generated by the COST in a Vickery Commons economy could be significantly greater than revenue generated from property taxes today; taxes would be levied on the true value of assets to individuals, rather than from imperfect appraisals of such assets by adversely incentivized third parties.

Is South Africa ready for a Radical Market?

A Vickery Commons infrastructure with a COST could be a promising way to manage agricultural lands acquired during colonization in South Africa for a number of reasons. Weyl and Posner’s proposal would ensure that the individuals who can generate the most value from the land will receive it, maintaining agricultural productivity, sustaining economic growth driven by foreign investments, and incentivizing service to previously underserved markets (particularly, encouraging more utilization of lands for housing). In addition, if the COST is paid as a dividend to the community, as a universal basic income, or as a way to pay for free higher education, another contentious topic in South African politics, the ill-gotten gains of holding colonized land will be paid back to the South African population. This would provide black South Africans retribution for the socioeconomic inequalities imposed upon them throughout colonization and apartheid. Lastly, the mechanics of the COST align strongly with rhetoric and actions concerning land reform in the recent past; it seems to echo the wishes of EFF leader Julius Malema and of black South Africans who have made claims on land which they previously inhabited.

Welfare Gains From The COST

In Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy, Glen Weyl and Eric Posner estimate the egalitarian benefit of applying a COST to all capital in the United States. Using a similar methodology, one can estimate the benefits a COST on South African agricultural commercial lands. Currently, the total value of commercial agricultural land in South Africa is $18 billion. At the rate of roughly 7% annually that is conjectured to be near-optimal (the $\tau_{eff}$ displayed in Figure 1) levying an additional COST tax on the value of land would leave the South African people with 1.26 billion dollars of additional revenue which could be set aside to completely fund progressive initiatives further diminishing inequality within the nation (free higher education for ambitious low-income South Africans, universal basic income to give the labor force time to reskill for the new economy). While the lower bound of expected tax revenue would be modest, Weyl and Posner project that the asking price of capital in a radical market economy would triple the total value of all land, (as individuals’ true value of capital is higher than the market value in a market in which sales are voluntary) which would in turn triple tax revenue.

Malema’s Own Words

Julius Malema is a controversial figure in South African politics, and is perceived to be quite the radical himself. However, when it comes to discussion of what he intends to do with the land once it is expropriated, his own words suggest that he is quite open to use of the land taking place in a market ecosystem. He has emphasized “people say when the land is in the hands of the state‚ there will not be investors. It is a myth. It is wrong.” He cites facilities owned by the state such as uShaka Marine World, a marine theme park, as examples of state-owned land that has not sacrificed all investment efficiency, and stresses that an effective solution to the land disparity will not involve a departure from private land investment. In addition, he has also commented that the main targets of expropriation should be land that is inappropriately utilized due to the high social cost of holding wealth. In March of 2018, he stated that farmers should continue to work their land “uninterrupted”, but that those parts that are lying idle must be “redistributed by the state”. He elaborates that the idling parts of farms should be relocated to those who will use it for production, signaling that he wishes to use land expropriation to drastically improve allocative efficiency, an ends to which William Vickery would strongly agree.

While it is clear that the ends of Julius Malema’s land expropriation plan mirror the ends of a Radical Market infrastructure like the Vickery Commons, it is not clear that Malema, or the EFF are the slightest bit flexible on the means. Malema strongly believes that land is a public good, and thus, the government should be in charge of determining who is best equipped to use it. On the other hand, the Vickery Commons, proposed by Posner and Weyl suggests that the public nature of land does not imply that its ownership must be monopolized by the state, but rather, that it should be decentralized as much as possible with dividends on its profits being paid back to support equal economic opportunity for all permanent residents. This divergence is stark, but it would definitely be worthwhile explore which methodology would better achieve their shared aim of significant welfare improvement. A cursory glance, within the context of recent history, suggests the free-market solution to this historically racial holdout problem more powerfully improves efficiency than a solution implemented, enforced, and micro-managed, by a tragically imperfect state.

Next Steps

In future blog posts, I would be interesting in exploring the feasibility of a using a COST for redistributing land wealth amongst South Africans, and as an alternative to land expropriation without compensation. I would also like to explore whether COST is in alignment with the South African constitution, and more closely estimate the exact welfare gains that could be achieved using the mechanism. Stay tuned!